People say one should water his trees when the top layer looks dry but i fail to understand what happens to the lower layers as it's out of sight. What if the lower layer is still saturated with water but the top soil is dry. How to know what going on in the lower layers?

This a mechanical story of cohesion, adhesion and capillary action. Water

adheres to the soil, but it also

coheres to itself. A well draining pot will draw water out by cohesive force, like straining tea of coffee, simple gravity. The water that stays behind is locked inside the particles, adhesion, if those particles make contact with each other, water can cohere to itself again; capilary motion takes place. Cohesion and gravity act like connecting two droplets on a foggy window; they make a bigger droplet and gravity starts working. In the capilary sense: a sponge can fill itself to the top if you put the bottom in a cup of water, just like our soil particles act. But this capilary action only works if all particles make contact and if the soil particles have a stronger adhesive force than gravity (more pores = more force.. Water doesn't stick to metal, it does stick to rock, and it sticks even better to sponges).

If the particles don't make contact, every soil particle has it's own water table inside of itself, if water can enter. If they don't make contact, this means they're surrounded by air and they will start evaporating water, creating a damp environment around them.

The Japanese took this physical behavior of water and soil particles to the next level: coarse particles on the bottom so cohesion will occur and draw out most of the water AND let a lot of air in by replacement of substance (if you remove water, you get air, to get air out, just add water). The smaller particles up in the top layer are there to actually hold water for roughly a day. We give our plants a multitude of 'total pot volume' of water, just so those cohesive forces can work their magic. My pots are 250mL in some cases, I water them with roughly 1000mL.

If a soil is well composed - and it rarely is perfect - then it should dry out on the bottom by drawing in air and by the forces of gravity,

and it should dry on the top because of evaporation (and adhesive forces from the water leaving the pot on the bottom). So a well composed soil should roughly dry as fast on the top as it dries on the bottom.

Our plants have less issues in colanders because here the evaporation takes place on six sides instead of one (and the pot holes). Only the center of the pot stays damp a bit longer than the rest.

Unglazed pots for conifers are not just used because they look good, the lack of a glaze also helps water evaporate on all sides, albeit a bit slower compared to a colander. Everyone eventually gets salt buildup on their unglazed pots because of this.

If your lower layer is saturated with water, it shouldn't pool! If it pools, then gravity doesn't work and you'll end up with a dead tree. That's why we all want holes in our pots. Pooling = lack of air = suffocation and fermentation = anaerobic microbe secretions and anaerobic pathogens = dead plant.

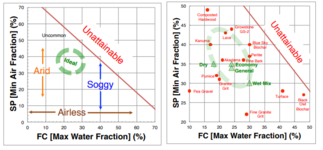

The whole "fast draining but water retentive" phrasing is kind of a mind fuck, but once you understand the mechanics, it starts getting fun to play with it.

Some of these forces can be bypassed by surfactants too! A super dry soil will be water repellent, a drop of soap will fix that issue right away.